Marxism Today - A Retrospective

The Communist Party of Great Britain was the overtly Communist group in the UK’s history. It was once very influential over trade unionist politics, had hundreds of local councillors to its name, and even a handful of MPs. Until the late 1960s, the party was a dedicated ally to the Soviet Union, willing to go against the grain of British politics. It came out against British involvement in WW2 (until the Soviets were invaded) and supported the suppression of the 1956 Hungarian uprising.

This support was in no small part, especially in the early years, due to the fact that the Party received significant financial support from the Soviet Union, far outweighing its relevance in British politics. Britain was still one of the world’s superpowers, despite being rapidly usurped by the USA and USSR, so the Soviets saw some use in having a friendly party representing their interests in the UK.

However, a split began to seem inevitable, for two main reasons. Firstly, the Soviet’s image for world socialism was becoming less and less appealing. In the 40s and 50s, Soviet-backed regimes popped up throughout Asia, Eastern Europe and the Global South. However, this was soon followed by infighting and division; the Sino-Soviet Split, Khruschev’s denouncement of Stalin’s regime, and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia to name just three.

Furthermore, in Western Europe, a new generation of communists came up with conflicting views to their predecessors. Many were Maoists, believing in the Chinese, rather than Soviet, road to socialism. Others were Trotskyites, attracted by an internationalist vision of revolutionary communism that criticised the contemporary Soviet Union. Whilst they differed greatly from each other and anti-revisionists, they agreed that Class was transcendentally important, and that violent revolution was both necessary and inevitable.

Thirdly, were the Eurocommunists, who believed that socialists should form broad alliances with social activists to create a broad appetite for change. They generally believed that democratic revolution (using established democracy to implement political, social and economic change) was preferable to armed uprisings. They were attacked by orthodox Leninists, Maoists and Trotskyites alike for being insufficiently radical and failing to centre the working class in their politics.

In the 1970s, there was debate in the CP over which path suited it best. Both the Maoists and Trotskyists had abandoned the party, but there was still a significant faction sympathetic to the Eurocommunist vision of broad social alliances. This, technically, went against party policy of democratic centralism (where, once a policy was decided upon, no further debate will be held), yet the party was not strong or unified enough to enforce this.

In 1977, the CP, guided by recently-appointed General Secretary Gordon McLennan, conceded to the Eurocommunists. They released a new revision of Britain’s Road to Socialism, a manifesto nearly as old as the party itself, giving it a Eurocommunist spin. This, finally, is where Marxism Today came onto the scene as a significant force in its own right; McLennan appointed Martin Jacques as editor.

Before ’77, Marxism Today was tightly controlled by the CP’s executive; and was fairly hostile to the Eurocommunist movement. It had little reach (or appeal) outside of the party itself. However, once Jacques (pictured right) got on board, he steered the publication into new waters. He was a long-standing member of the party, sat on the central committee, and was the one who McLennan tapped to draft the new Britain’s Road revision; his selection seemed natural for Marxism Today.

It could have been fairly predicted that the magazine’s new direction would attract a wider readership; Eurocommunism is inherently inclusive to a range of social groups. What could not have been predicted was how successful it was. In 1981 the magazine became available at newsagents, and by the mid-‘80s, Marxism Today was wildly popular. It’s circulation easily outstripped both the CP’s own membership and its daily paper, the more orthodox Morning Star.

Many major leftist authors and politicians were regular contributors to Marxism Today. Eric Hobsbawm and Stuart Hall were two of the most influential British writers of the time with international followings, and they were regular contributors to the magazine. Hall actually coined the term “Thatcherism” in a 1979 article. Tony Benn, who represented the socialist wing of the Labour Party throughout the 80s, wrote articles explaining his position on the party’s relationship with Marxism. These influential writers, among others, saw Marxism Today as an important outlet for discussion.

Andy Croft on Marxism Today:

As Andy says, the key strengths of Marxism Today was its willingness to ask difficult questions, and accept input from people across the socialist ecosystem without straying too far away from its central goal; developing a dialog between the Eurocommunists, social reformers and democratic socialists. This followed the teachings of Antonio Gramsci, the ideological forerunner of the Eurocommunist movement, who argued that compromise and co-operation between working class socialists and other groups with similar objectives would be necessary to achieve revolution.

Of course, Marxism Today had its weaknesses. According to Jacques it had two key issues: "Firstly, its failure to lay sufficient stress on core values of the left like equity and the notion of the public… But closest to my heart is the weakness of Marxism Today on the world outside the west: it was overwhelmingly western-centric. And, not unrelated, was its failure to address race and ethnicity, without which it is not possible to understand the world in which we live.”

Naturally, the magazine’s radical direction and popularity attracted dissent from the anti-Eurocommunist wing of the Communist Party. The editors of Morning Star, who remained anti-revisionist, claimed it was not authentically Marxist and overly navel-gazing – interested in long-winded debate rather than direct calls to action. There was a shred of truth in this, of course, but there was no reason to believe the magazine was built on a foundation of sand, yet.

So, what happened then? The issues, a lack of core aims and intersectionality, were manageable, and the magazine remained popular and relevant for many years. Yet, the December 1991 issue was their last. One obvious cause of this was the international scene; 1989-91 was a period of disappointment and collapse in the socialist world. Tiananmen Square, the revolutions in Eastern Europe and the impending collapse of the Soviet Union all damaged the image of Marxism’s viability.

Of course, Marxism Today had long stood in opposition to the PRC, Warsaw Pact, and Soviet Union; their failures did not necessarily have to reflect on the magazine. Nevertheless, after 1989, magazine sales slumped slightly, and it became harder to justify the title. Much of the general public believed Marxism Today’s central question (what can Marxism mean in the modern world?) had been answered; it was a relic of the past.

At the same time, the magazine itself had grown away from Marxism as a central guiding principal. By 1991, Marxism Today could have more appropriately called something like Democracy Today, or even Gramscianism Today. True to form, the Communist Party, which had followed the magazine’s ideological path in the late 80s, schismed, transforming into “the Democratic Left”.

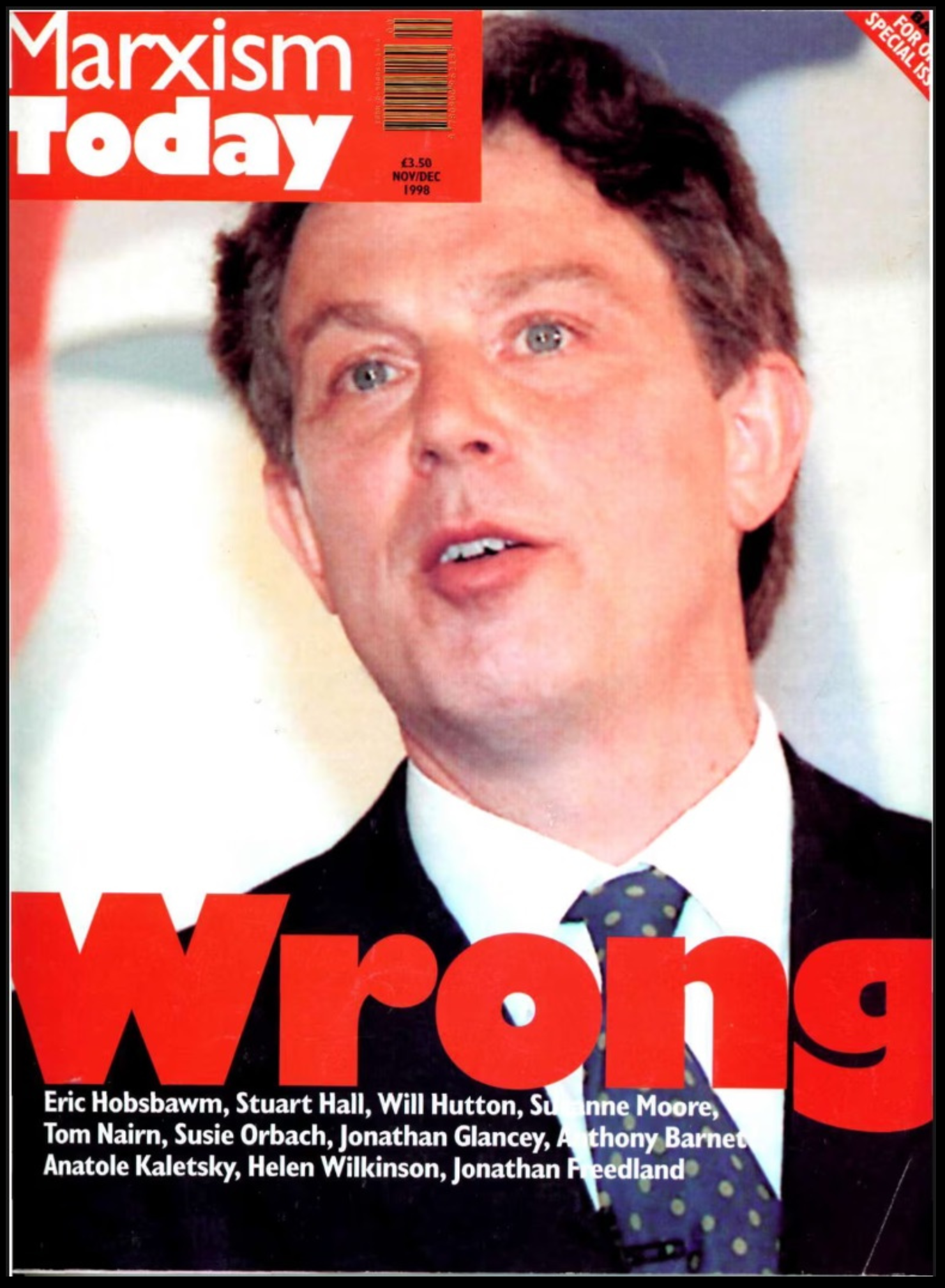

There was one last hurrah in 1998, when a special edition was released to criticise Tony Blair and his push to move the Labour Party away from socialism. Blairism aligned with Marxism Today’s modernist outlook, yet it embraced capitalism to a radical extent for the Labour Party. This special edition did not herald a relaunch for the magazine, however. For almost three decades now, the Marxism Today brand has been dormant. As for Jacques, after the magazine broke up, he went on to co-found Demos, a policy think tank, and began leaning more into academics, interested in China and its role as a growing economic and cultural superpower.

What can we learn from the Marxism Today story? Firstly, its success tells us that people are generally interested in the free exchange of good ideas, especially if they present an appealing alternative to both the status quo and radicalism. Secondly, no idea was sacred; by 1991, influenced by the magazine, the CP transformed from a Marxist-Leninist organisation to one that was barely Marxist and not at all Leninist. Thirdly, whilst the free exchange of ideas is brilliant, it’s a pretty difficult to organise effectively around, especially once the one principle all agree on (socialism) has seemingly been discredited by events beyond your control.