What Happened To Militant?

Most people who followed British politics in the 80s remember “the Militant”. It was a vaguely sinister spectre floating on the left of the Labour Party; Communists hell-bent on infiltrating mainstream politics and transforming Britain into a Workers’ Republic. It had a charismatic leader that ruled Liverpool with an iron fist and a shadowy circle of elders that steered the group from behind the scenes. Of course, it was never this dire. Like all other revolutionary groups in the UK, the Militant Tendency never managed to become a major player in the British political ecosystem. It did, however, arguably get closer than any before or since. To explain, we first need to travel some decades earlier.

A Long Origin Story

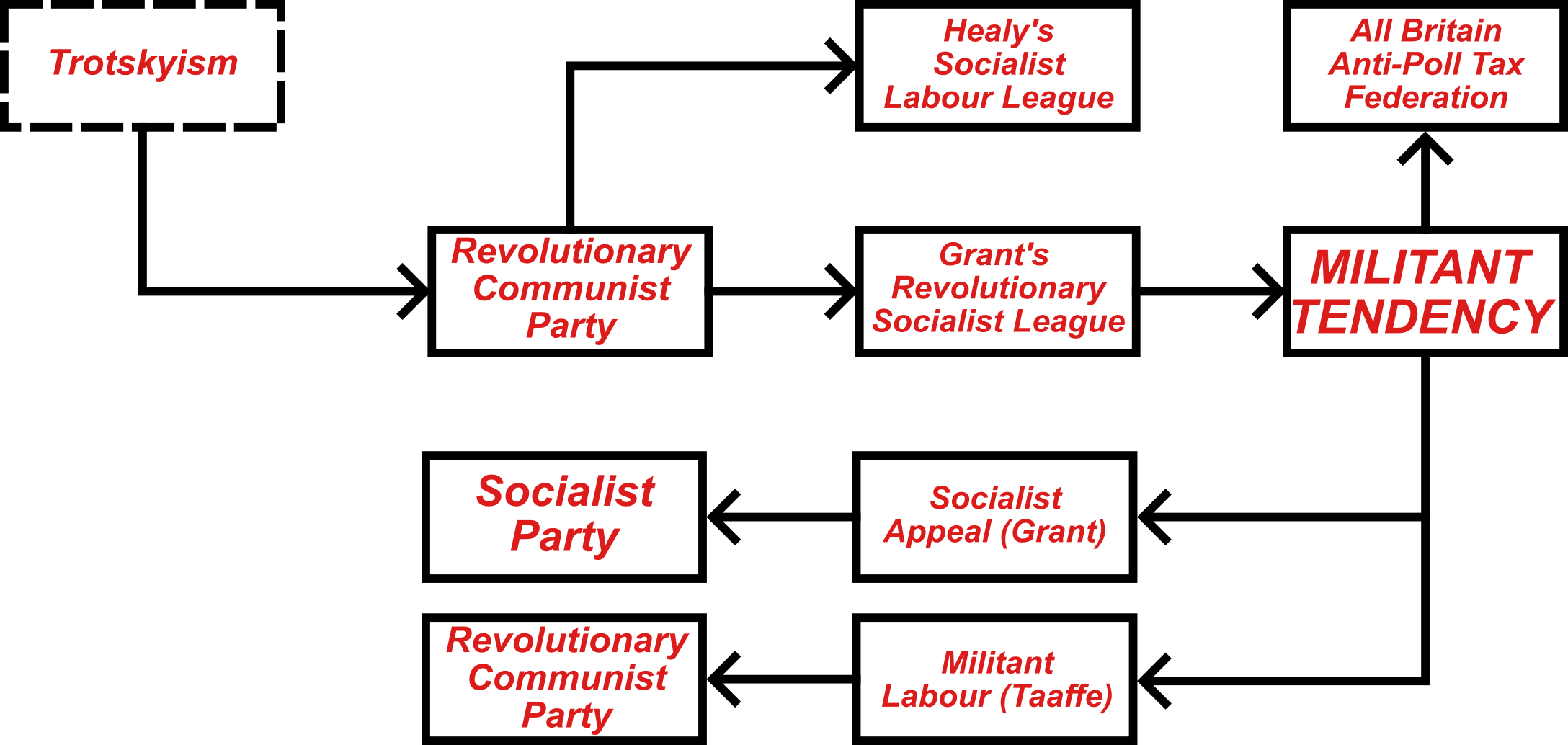

Leon Trotsky was a Soviet revolutionary, and a contemporary of Lenin and Stalin. Many saw him as Lenin’s heir apparent, yet Stalin was able to manoeuvre himself into power, forcing Trotsky to flee the USSR. Trotsky’s ideology was based on international “permanent revolution”. This was in odds with Stalin’s “socialism in one country”. This schism caused endless reverberations (not least the 1940 assassination of Trotsky), but for our purposes it meant that Trotskyites would never again align themselves with the USSR.

In the 1940s, a group of Trotskyites came together to form the Revolutionary Communist Party, an implicit rival to the much larger, Soviet-backed Communist Party of Great Britain. It was led, among others, by Ted Grant (pictured left, born Isaac Blank in South Africa) and Gerry Healy. By 1950, the party had its own schism. Healy was in favour of entryism, meaning the infiltration of the Labour Party to transform it into a revolutionary socialist organisation, whilst Grant was opposed. Healy went on to form his own party, whilst Grant’s faction transformed itself into the Revolutionary Socialist League.

Despite the fact that the RCP split took place because of their aversion to entryism, the League began pursuing that very same policy in the late 50s. This can be viewed as a matter of circumstance; all of a sudden the RCP had a method, Labour Party had just relaunched their Young Socialists organisation, and a reason, there was danger of the Labour Party to swing right, to change its mind on entryism. In the 60s, they began publishing Militant, a title that may or may not have been stolen from the American SWP’s publication. “Militant”, which, to be fair, is far catchier than “the Revolutionary Socialist League”, soon stuck, and the group renamed itself to the Militant Tendency in 1964.

Militant: How and Why

Early Militant had two primary tactics. Firstly, they worked to take control of the Labour Party Young Socialists, the party’s youth section. As its name suggests, the LPYS swung a bit further to the left than the party mainstream, making it a good target for Militant, which had a fairly young base. By 1972, Militant and its fellow-travellers made up a majority of the organisation. They were, however, unable to take control of NOLS, the Party’s student organisation. This is what drew the party’s attention; they directed Reg Underhill to produce a report on Militant. This, released in 1975, exposed Militant’s internal workings.

Their other tactic, aside from the LPYS, was to be very active in local sections of the Labour Party. They would build up support, often covertly, until they made up the majority of active Labour Party members in a local area. This gave them the ability to influence local policy, fund allocation, and candidate selection. Neil Kinnock explains his perspective of the tactic:

Militant grew quickly through these tactics, becoming one of the largest organisations within the Labour Party. Andy Ward, who I spoke to in July, talked about how there were a lot of socialist organisations floating around in the 1980s, such as the International Socialists and Socialist Workers’ Party. However, the Militant Tendency appealed more than the others because, according to Andy, it had a more robust organisation, strategy, and seemed more significant than the others. It seemed like a good alternative to not just the Labour Party, but the Communist Party of Great Britain. Steve Nally concurs on the appeal of Militant:

The Underhill report also revealed Militant’s aims to the party as a whole. Outwardly, they pushed for greater democracy within the Labour Party and industrial nationalisation. Internally, though, they saw the Labour Party as a useful vehicle for political revolution. It was the only group with broad support from the working class and had strong ties to all major trade unions.

By this time, the group was led by the “Editorial Board”, a group that was technically only responsible for the Militant newspaper but actually held sway over Militant activists and local politicians. The exact make-up of the Editorial Board shifted over time, but the two most important members were Ted Grant (Political Secretary) and Peter Taafe (National Secretary). Whilst Grant provided ideological coherence, Taafe directed Militant’s strategy; they were a formidable team. Kinnock describes how he saw the EB:

This concerned the Labour Party leadership – yet they refused to act against Militant. They had only just got rid of the despised “Proscribed List”, a policy from the 1950s that allowed the Party to unilaterally bar people associated with certain organisations on the left. Nevertheless, through the 1970s, Militant continued to build its base among the LPYS and local parties, reaching their peak of power in the early 1980s.

Inflection Point: Liverpool

Militant was becoming a significant faction within the Labour Party. In response, a successor to the Underhill report was released in June 1982, called the Howard-Hughes inquiry. This argued that the group broke party rules; Militant’s revolutionary aims were at odds with the party’s constitution. Because this very same constitution, Labour could not yet exorcise Militant from the party. All they could do was expel the five Editorial Board members, including Grant and Taafe, in February 1983.

This did very little, at least in the short term. In May, Labour won control of Liverpool city council. As the local Labour Party was dominated by Militant, this was their win. Two months later, Militant got its first two MPs; Terry Fields in Liverpool and Dave Nellist in Coventry. This string of successes, despite opposition from the party leadership, many trade unions, the mainstream press and opposition parties is a testament to their efficacy in the period.

The big confrontation between Militant and the Tories came in ’85. The government had cut the amount of money they would give to cities across the UK; the local councils would have to either raise taxes or cut services to stay in the green. Militant and Hatton decided to blatantly ignore this; they would do neither and run an illegal “deficit budget”, where they spent more money than they made.

This was opposed, naturally, by the Thatcher government, but also Kinnock’s Labour Party. Their position was vindicated when the national government refused to back down, and it became increasingly evident that the council would not be able to pay its employees. They were forced to send out notices to 30,000 people, admitting that in ninety days there would be made redundant.

To this day, Hatton and those involved claim this was a bluff, a strategy to release some pressure on the council. Many of the workers did not see it that way; they were more interested in getting paid than whatever byzantine plan Liverpool Militant was working on. Furthermore, both the Labour and Militant leadership put increasing pressure to put an end to this doomed rebellion. Eventually, facing opposition from both above and below, the council took out massive loans to balance the budget.

This may seem like a strange strategy for Militant, bogging itself down in a doomed battle over council funds, but there was some logic to it. Militant had never been so influential in the Labour Party, and there was widespread opposition to Thatcherite cuts in the country. If their influence was slightly stronger, or opposition was slightly more organised, they may well have succeeded in transforming a local struggle into a national opportunity for the Labour left.

Kinnock Strikes Back

Neil Kinnock was a long-standing member of the Labour Party, becoming an MP at around the same time that Militant became active within the party. His position on the group can be summed up in his re-occurring mantra “they want power in the party, rather than power for the party”. He believed that Militant’s mission to transform the Labour Party was, first and foremost, a strategic mistake. Kinnock has a philosophy on achieving power politically:

Kinnock wanted to go after Militant as soon as he took control of the party, although he did not feel like he would have the support of the party; many were satisfied with just the expulsion of the Editorial Board. After 1985 and the chaos in Liverpool, Kinnock had the excuse to fully crack down on the group within the party. Whilst many were still anxious about the legacy of the Proscribed List, many more recognised that the party was no longer a space for revolutionary Trotskyists. Kinnock explains why he acted when he did:

By 1986, Kinnock was able to expel Hatton. Despite the Editorial Board being, in actuality, more influential in the party, Hatton was known nationally; his expulsion made a far bigger splash than theirs. This was a major symbolic blow to the left; aside from Arthur Scargill, Kinnock’s other big left flank enemy, Hatton was probably the most famous socialist in politics that Kinnock could not reign in.

For the rest of the decade, Kinnock continued to lead the party in their purges of Militant and its supporters. If the attempt was to present Labour as a more moderate party that did not accept radicalism, it did not work perfectly. The protracted struggle to purge Militant from Labour gave the image of a party at war with itself, one that was not ready for government. According to Alan Woods, a Militant member who worked closely with Ted Grant:

“No sooner had the erstwhile “Left” Kinnock grabbed the labour leadership from the faltering hands of his ageing predecessor, than he declared all-out war on the Labour Left headed by Tony Benn up to whose knees he did not reach, politically, intellectually, morally or in any other respect. Before annihilating the Bennite left he first had to deal with the militant tendency. Kinnock knew that it was the Marxists of Militant who gave backbone to the Lefts.” (Alan Woods, Ted Grant – The Permanent Revolutionary) To Militant members, Kinnock only went for Militant as they acted as a vanguard against the Labour right.

For some, the fall of Militant was not so dramatic, rather a result of a slower, steadier decline. Andy Ward, who had already begun moving away from the Labour Party in the mid-80s, believed that Militant was already in a precarious position before Kinnock’s crackdowns. He believed he would have more success at the local level through the mainstream Labour Party, and that being a Militant member was too much of a commitment. This sentiment is echoed by some other ex-Militants.

Militant: Not Yet Dead?

In the early 90s, Militant, which still had many members within the Labour Party, was involved in the campaign against the hated Poll Tax, Margaret Thatcher’s initiative to instate a flat tax on every adult in the UK in order to fund her tax cuts. Militant, still sore from the loss in Liverpool, weren’t going to let this happen without a fight.

Militant members were instrumental in founding the All Britain Anti-Poll Tax Federation and set up a series of Anti-Poll Tax Unions across the country to organise and assist non-payers. This tactic was massively successful, galvanising popular support against Thatcher which majorly contributed to her defeat. Steve Nally, who was secretary of the Federation explains:

Eventually, Militant tried a new tack, moving outside the Labour Party. They successfully endorsed a handful of candidates in council elections and unsuccessfully endorsed Lesley Mahmood for a Liverpool constituency. There was division in the party whether this “open turn” was a good idea which led, of course to a schism.

Ted Grant and his minority faction maintained that Militant should work within the Labour Party, despite the repression. In 1992 they split off and founded Socialist Appeal, which recently transformed into the Revolutionary Communist Party. Peter Taaffe and his majority faction, meanwhile, supported transforming Militant into a political party in its own right; they thought Labour was a lost cause. In 1997, they renamed itself the Socialist Party. Both the RCP and SP continue to this day, albeit on the fringes.

What’s the point?

So, what can we learn from Militant’s slow rise and rapid fall? There are two prevailing narratives. The most popular one, that I proposed at the start of the article, is that Militant was a covert revolutionary sect that threatened the integrity of the Labour Party, they ruled Liverpool dictatorially, and Kinnock’s actions against them were justified. On the other hand, those nostalgic for Militant argue that it presented a genuine alternate path for the Labour Party, and its repression paved the way for the Party’s neoliberal turn in the late 90s.

I think there is a third way to look at it. British Trotskyites were a small, fragmented community in the 1960s, without the benefit of a unifying organisation like the CPGB. Simultaneously, the Labour Party was going through a period of openness, it was cautiously entertaining a dialog with Marxists. Thus, Grant’s faction had reason to believe they would be accepted; if not by the leadership, then the rank-and-file.

The struggle came from balancing Militant’s willingness to work as an aspect of the party, and their ambition. Despite Militant’s hopes, the majority of the party were comfortably social democrats, unwilling or unable to be convinced to shift leftwards. Liverpool ’83 was, therefore, such a fiasco because Militant, influenced by Hatton, jumped the shark. They made a power-play before they had any widespread influence beyond Liverpool city limits. This unforced error, whilst understandable on principal (the socialist group would naturally oppose Thatcherite cuts), was perfectly mistimed; it painted a target on their back that Neil Kinnock, green and willing to prove himself, could aim for. The result was a public fall that helped establish a new normal in the Labour Party against co-operating with the left.

The question to ask now, of course, is whether Militant was correct that working within the Labour Party was the way forward? History would seem to suggest that the party was on the move rightward, possibly suggesting that, even if there wasn’t such a blow-out in Liverpool, Militant would be left behind. This article is being written at a time when the socialists elements remaining in the Labour Party are on their way to forge their own course; a course, mind you, supported by Militant’s successors, the SP and RCP. Will Corbyn and Sultana’s party be the new Militant, or will it thrive free of the confines of Labour? Time will tell.